Holcim Awards Europe, Bronze:

The Commons, 2014

Ecological neighbourhood in Vienna, Austria

As winners of the ‘Holcim Bronze Award’ in Europe, our interview and project have been published in the book ‘Sustainable Construction 2014/2015’ alongside with the winner projects in the rest of regions and the Holcim Global Awards.

Our ecologic neighbourhood proposal in Vienna was selected between over 6000 projects presented in 152 countries. You can find more information on the 2014-2015 Holcim Sustainable Construction Award in the following link:

http://www.lafargeholcim-foundation.org/Projects/the-commons

And to know more on the awarded project:

http://arenasbasabepalacios.com/blog/2011/09/14/desarrollo-europan-10-viena/

Here you have the interview published in: SCHWARZ, Edward. Fourth Holcim Awards. Regional and global Holcim Awards competitions for sustainable construction projects and visions 2014/2015. Zurich: Holcim Sustainable Construction Press, 2015.

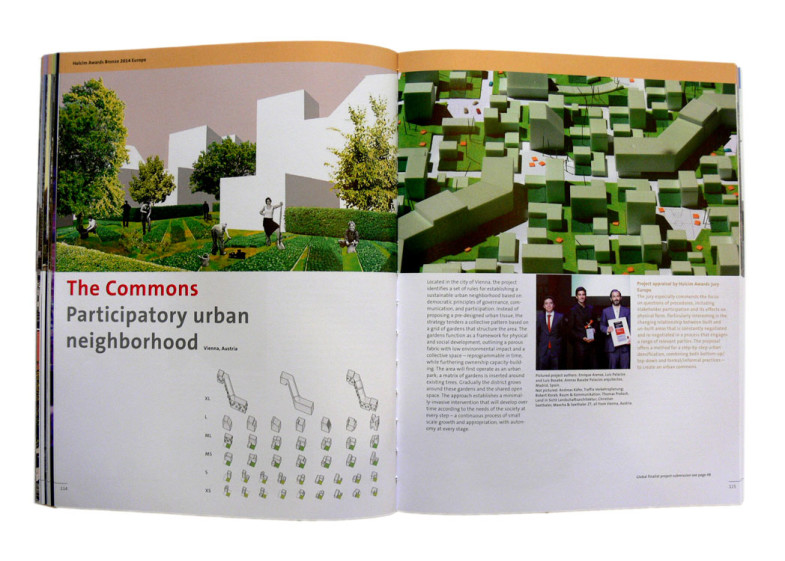

The Madrid-based architectural firm arenas basabe palacios developed a hands-on concept for the redevelopment of an abandoned site in Vienna – one which represents a new form of garden city.

Most large cities have long been built – especially those with a lengthy and important history such as the Austrian capital, Vienna. Disused sites for something completely new to be built are a special challenge and must be treated with care.

Such a challenge is an 11-hectare site in Vienna in the Rosenhügel district in the southwestern part of the city. It is surrounded by railroad tracks, a neighborhood of stand-alone houses, a cemetery, and an area of allotment gardens. The site was first occupied by a pig farm, then by the Federal Office for Protection of Pets Against Virus Infection – and ultimately it was abandoned.

Today the land belongs to the state-run real estate company Austria Real Estate (ARE), which intends to build housing on the site as part of a larger district development project. In January 2009 ARE launched the international design competition EUROPAN 10 for this housing project. The young architectural firm arenas basabe palacios, based in Madrid, took part. The three principals, Enrique Arenas, Luis Basabe, and Luis Palacios, have been working together since 2006.

Why did your office decide to take up a project in Austria?

Luis Palacios: We see EUROPAN as less of a competition and more of a congress for young architects to exchange their ideas about the city. At EUROPAN 9 we won with a project in Kapfenberg, Austria. The project was never realized, because the small town was not ready to take the next step. For EUROPAN 10, we decided to participate again in Austria with another project – perhaps it would work on a second try…

Luis Basabe: Our office has worked in various ways on situations that are socially very complex; we call this our red line. At the same time, there is a green line that runs through our work, often applying to suburban contexts. Our prize-winning project in Kapfenberg revolves around a pronounced suburban situation: The village with its train station had become a bedroom community. We found an analogous situation at this derelict site in the southwest of Vienna.

What was the ARE brief?

Luis Basabe: EUROPAN usually issues very open briefs, because they often choose places for the competition where no one could so far figure out what to do. That makes it particularly interesting for us. So the program was flexible – only residential use was prescribed – and we could have proposed practically anything.

When master-planning large sites such as this one, designers typically concentrate the program into large buildings surrounded by large green areas and other public spaces. But here, the authors sought a solution whose smaller scale is more suited to people and the place. The Spanish architects proposed not only a housing development but a concept with a high level of abstraction – their master plan looks playful, reminiscent of those popular board games in which a schematically displayed landscape is to be colonized following a set of rules. The concept is based on an overall grid of gardens upon which various building types, from stand-alone houses to large apartment buildings are organized. The result is a new type of garden city, one which will receive its final face only after the various players have erected their buildings over time.

How did this hands-on concept arise?

Enrique Arenas: Many entries in architectural and urban planning competitions are geometrically based. We believe, however, that the diversity of complex issues in urban development must be addressed not formally but strategically. That’s why we always like to start our projects by asking what role the architect should assume in each specific case. Would it be better here not to build at all? Should the architect design everything or rather coordinate the collaboration of a team? In this project, our contributions are a first step following which many different players will negotiate further steps. There must be inherent flexibility because we also know that our plans often will not be built exactly as we have proposed.

Luis Palacios: For us, the relationship between research and competition projects is important. The idea for our garden city arose through workshops on urban development we carried out in India. We learned how cities evolve there.

Luis Basabe: In India, you will hardly recognize an informal settlement ten years later, because so many changes and expansions occur, and it’s the same with the designed buildings too. Such ideas can also be applied to the contemporary European city.

But the context is completely different. How can this understanding apply in Vienna?

Luis Palacios: In Europe, we use the mechanism of the land parcel. We divide land into plots and say: Everything within these boundaries belongs to me; here I can do what I please. Things work differently in India. There, buildings expand to the wall of the neighbor’s house. Then negotiations begin. For example, where do we have to allow room for traffic? We wanted to bring some of this concept into contemporary suburban development in Europe.

The architects divided the site of The Commons into a grid of gardens which would serve as a framework for urban and social development. 33 percent of the land area will be covered with nearly 1,000 residential units, 10 percent is reserved for private gardens, and 57 percent will remain as common green space. The architects defined an urban code for all the gardens. Private owners and investors can buy garden plots and build around them, not inside. They call it ‘extroverted plots’. The unbuilt areas, or “the commons,” remain open to everyone. Thus, the actions of the owners will determine the appearance of the public space and of the whole neighborhood.

In your plan, why did you begin with the gardens and not with buildings?

Enrique Arenas: The structure should be defined not by buildings but by the green spaces. The gardens are the playing board – or the hardware for the project. Once the playing field is defined, we need rules for interaction, or the software. Our garden city also has rules and playing cards. They define how things can develop and which relationships can arise among citizens.

After defining the playing field and the rules, how much freedom do the people have when they build?

Luis Basabe: The owners are free to decide on the volume and the design of their buildings.

The future residents have not been included in the planning process. Can we still call this a participatory design?

Luis Basabe: Normally, the planning phase is participatory in the sense of asking people what they want, and of course this is important. But the issue is not only to decide how the city should be, but also to build the city together and to share living in it. The production of cities also requires participation – and this is often forgotten. A good example of participation might be something like ten garden owners pooling their land to plan something jointly. These participants didn’t determine the concept, but the concept is flexible enough to accommodate their various needs.

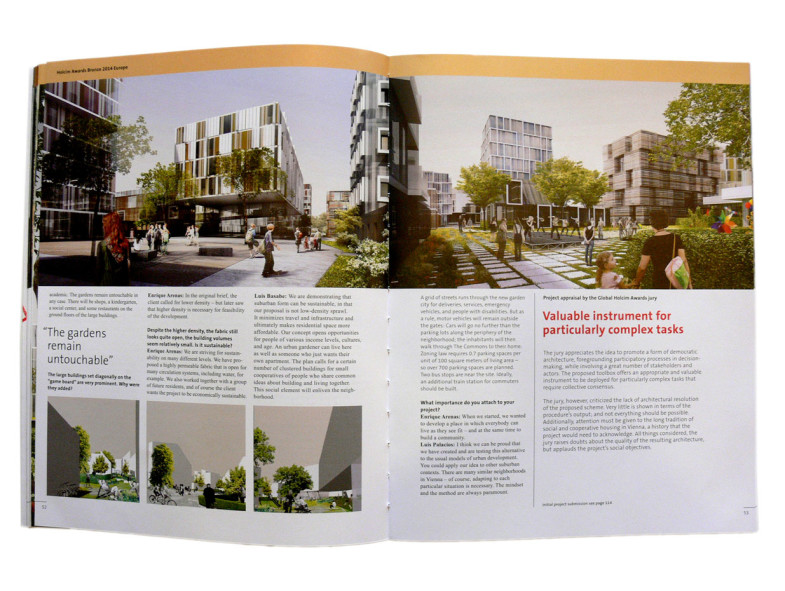

The flexibility of the Spanish architects’ concept has already been proven. The project has been developed in further detail. Workshops on mobility, landscape design, energy, and other aspects have brought The Commons into a form that will be implemented in 2016. The client demanded much higher density than the original proposal provided, so some large buildings have been added. In addition, an eight-story building was removed from the garden neighborhood because the opinion of the neighbors, that have been joined the collaborative process in a recent stage.

Your plan met some resistance and was adapted in response to a variety of critical comments. How much is left of the original concept?

Luis Basabe: It’s still one hundred percent our idea, it’s simply been upgraded. The reality now looks somewhat different than our original plan – not worse, but a bit less radical and academic. The gardens remain untouchable in any case. There will be shops, a kindergarten, a social center, and some restaurants on the ground floors of the large buildings.

The large buildings set diagonally on the “game board” are very prominent. Why were they added?

Enrique Arenas: In the original brief, the client called for lower density – but later saw that higher density is necessary for feasibility of the development.

Despite the higher density, the fabric still looks quite open, the building volumes seem relatively small. Is it sustainable?

Enrique Arenas: We are striving for sustainability on many different levels. We have proposed a highly permeable fabric that is open for many circulation systems, including water, for example. We also worked together with a group of future residents, and of course the client wants the project to be economically sustainable.

Luis Basabe: We are demonstrating that suburban form can be sustainable, in that our proposal is not low-density sprawl. It minimizes travel and infrastructure and ultimately makes residential space more affordable. Our concept opens opportunities for people of various income levels, cultures, and age. An urban gardener can live here as well as someone who just wants their own apartment. The plan calls for a certain number of clustered buildings for small cooperatives of people who share common ideas about building and living together. This social element will enliven the neighborhood.

A grid of streets runs through the new garden city for deliveries, services, emergency vehicles, and people with disabilities. But as a rule, motor vehicles will remain outside the gates: Cars will go no further than the parking lots along the periphery of the neighborhood; the inhabitants will then walk through The Commons to their home. Zoning law requires 0.7 parking spaces per unit of 100 square meters of living area – so over 700 parking spaces are planned. Two bus stops are near the site. Ideally, an additional train station for commuters should be built.

What importance do you attach to your project?

Enrique Arenas: When we started, we wanted to develop a place in which everybody can live as they see fit – and at the same time to build a community.

Luis Palacios: I think we can be proud that we have created and are testing this alternative to the usual models of urban development. You could apply our idea to other suburban contexts. There are many similar neighborhoods in Vienna – of course, adapting to each particular situation is necessary. The mindset and the method are always paramount.